Self As Other By Xanthe Dobbie

“Art is not a mirror held up to reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.” – Berthold Brecht

Language shapes reality, but reality isn’t fixed.

The Western hetero-patriarchal tyranny of language positions self in opposition to other. This is a hierarchical binary – one which inherently places value on self over other. Such is true of countless other common pairings; man/woman, human/animal, human/machine, subject/object, mind/body – a Cartesian divide to uphold domination.

To shape alternative (fairer, better, queerer) futures, we must, as Donna Haraway put it, “find a way out of the maze of dualisms in which we have explained our bodies and our tools to ourselves” (1991, p. 67).

What happens when the self is also other? When these binaries begin to leak?

Self as a term – in the way that we know and use it – is a relatively new phenomenon. Relegated to the fanciful meanderings of poets in the 1800s, self didn’t enter common vernacular until the turn of the 20th Century. Coinciding with the introduction of other reductive terms like hetero- and homosexuality, we can blame psychoanalysis for the viral rise of self in all its modern rigidity.

To speak of self is of course to speak of identity – of the intersections of gender, sexuality, race, and class precariously housed in our bodies. Bodies in a state of flux. Bodies in relation to other bodies – responding to and shaping one another with each meeting.

Let us not dwell on identity politics.

Simply holding a marginalised identity and making art is not an innately radical or transgressive act. We must push beyond tokenism into structural destabilization, questioning the very fabric of the way our society has been constructed. Judith Butler would call this performativity – the socio-political assemblage of our performed identities – contextual selves.

Following Butler, in Queer theory, identity is imagined in terms of fragmentation, relationality and perpetual becoming – a playground for self and other to collide. Queer theorist Annamarie Jagose defines identity in poststructuralist terms as “an effect of identification with and against others: being ongoing and always incomplete, it is a process rather than a property” (1996, p.79). Here, “queer” is considered in its theoretical active tense as a verb – a queer(ed) identity is defined by what it does, not what it is. Selfhood is performance.

The varied contributions to the Self exhibition work to undermine (to queer) the apparent fixity of language and experience. These are entwined with significant and multi-faceted histories of queer and feminist practice. David Getsy writes, “the defining trait of ‘queer’ is its rejection of attempts to enforce (or value) normalcy. Within artistic practice, queer tactics and attitudes have energized artists who create work that flouts ‘common’ sense, that makes the private public and political, and that brashly embraces disruption as a tactic.” (2016, p. 12).

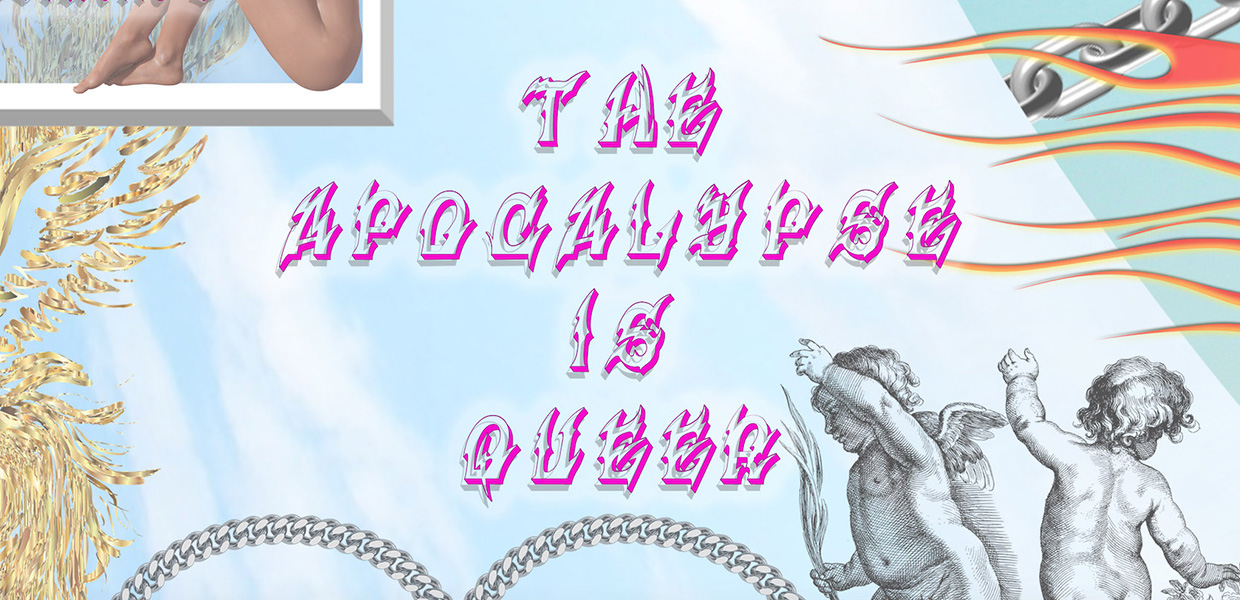

The works of Self disrupt. Each piece seeks to defamiliarize the familiar; collapse private and public; self and other. Jo Swepson’s The Lipstick Projections evokes a kind of Lynchian trauma-scape in the simple, absurdist repetition of applying make-up – a highly gendered act. Laith McGregor, Antoinette O’Brian and Fabian Pertzel’s works lean into productive discomfort, urging the viewer to unpack their preconceived notions of archetypal masculinity or femininity and to embrace the in-between. Stephen Garret calls into question the narrow trajectory of capital-H history in the Western Canon, while my own work proclaims, ‘The Apocalypse is Queer!’.

Queering form and expectation, each artwork is a porous gesture – an invitation (perhaps a provocation) for change in a post-truth world. Rebecca Schneider writes, “a gesture, like a wave, is at once an act composed in and capable of reiteration, but also an action extended, opening the possibility of future alteration” (2018, p. 286). By deconstructing ourselves, we begin to create space for other-selves; other-worlds; other-futures.

REFERENCES:

Brecht, B. (1964) Brecht on Theatre. Edited by J. Willett. Detroit: Methuen.

Butler, J. (2006) Gender Trouble. 3rd edn. New York: Routledge.

Getsy, D. (2016) ‘Introduction’, in Getsy, D. (ed.) Queer: Documents of Contemporary Art. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Whitechapel Gallery, The MIT Press.

Haraway, D. J. (1991) A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. London: Routledge.

Jagose, A. (1996) Queer theory: An introduction. New York: New York University Press.

Schneider, R. (2018) ‘That the past may yet have another future: Gesture in the times of hands up’, Theatre Journal, 70(3), pp. 285–306. doi: 10.1353/tj.2018.0056.

Words by Xanthe Dobbie © 2022

Image | Xanthe Dobbie Hands Across the Globe (detail) 2021, Silk print, 102 x 400cm