Public Art and Re-calibrating Culture by David Pledger

We live in a world in which the line between public space and private space is in a continual process of being re-written, and its impacts recalibrated. This kinetic process has implications for artistic practice.

In the online art world, for example, NFTs take an image from the public domain and, through blockchain technology, place it firmly in the domain of the private collector. It exists simultaneously in both public and private domains, and yet a single person owns the original, its provenance proven through technological innovation. It is a highly speculative area, still conceptual in many ways, massively impactful on the environment and now migrating to non-arts domains such as gaming and IP. NFTs are a sensational measure of the volatility of the public-private dichotomy in the non-physical world.

In the real world, in the world of physical space, the lines are no less blurry. Who owns a space? Why do they own it? How did they come to own it? If they own it, can they keep people out at the same time as letting others in? What does ‘private’, mean? If it’s a public space, what are the rules of being in that space? How many publics are there with an interest in the space, and how might they bring pressure to bear around its use? Do all the public own the space, or just certain segments of it?

A key organising principle of art-making is the establishment of context and its parameters, and an understanding of our complicity in that context. Occasionally, as artists and curators, we find ourselves in situations in which the politics are clear and uncluttered. Mostly, though, we find ourselves in contexts in which we have less agency than we first imagined, and are often complicit in a structure, a program or a circumstance that challenges our values as artists, as citizens, as human beings. These are very often the parameters of art-making in public spaces.

In public art, place is a generative prism through which an artist must eventually view their practice in order to identify and pursue a context and their complicity in its meaning, and meaning making.

Whether place is a nation, a state, a city, a region or suburb, it requires conceptual and cultural frameworks that crossover history with capital and ownership.

In a country like Australia, these are highly contested and conflicted spaces. After all, we live on unceded lands, ‘owned’ primarily by private people and public interests. Always underlying this is the map of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island Australia with its hundreds of nations and peoples. The ongoing contests around ownership of land are deeply connected to the cultural meanings of place for First Nations peoples.

For Australian artists exploring or practised in the making of art in public spaces, key questions persist: How does one respect the contested lands on which they work? How does art in a public space contribute to the meanings of that place? How do artists who are not from a place develop projects that respect and add meaning to the multiple entry points through which it is going to be experienced by people whose place it is, and people who are visiting.

In September, two Northern Rivers artists will be heading to Ōtautahi, Christchurch to undertake a month-long residency, Expansive Encounters, that has been framed in the context of post-disaster. Whilst it is true that creative recovery has significantly impacted the relationship between citizen-and-institution, artist-and-community, the private/public dichotomy of space persisted long before the effects of climate change reached tipping point.

When we think about the relationship between private and public spaces and the agency, role and position of art in these spaces we must contest the hegemonic narratives that have been sewn together to control access and use of land for centuries. The nature of this contest determines the collaborative tone, the appropriate artform and the cultural ‘frequency’ of our making.

In creating public art, the primary questions are determined not so much by what we are making but how we are making, and so while an artist’s process might contain the same basic dramaturgy, the key elements of their dramaturgy need to be reconfigured according to the protocols of process as opposed to production. This gives public art a radical spin.

Unlike the NFT, public art is not a commodity to be bought and sold at auction. Its value lies in ‘process’ or the ‘operating system of production’, not the thing produced.

Public art materialises through the collaborative interactions of community, artistic disciplines, sectors, cultures, histories and place. In the process of re-calibrating practice, artists working in public space end up re-calibrating culture.

Which means that making art in public spaces is not simply an artistic practice, it is a politico-cultural practice. The circles of meaning emanate outwards into and through society, creating all kinds of possibilities for change.

Once made, a public artwork is defined by how it ‘lives’ in the public space and how people relate to it. It projects a life beyond creation in the public sphere and into the meaning-making of culture and cultural production. It exists in the cultural imaginary of place. Its power is both concrete and metaphorical. Its presence may be temporary, but its effects are lasting.

Words by David Pledger © 2023

notyet.com.au

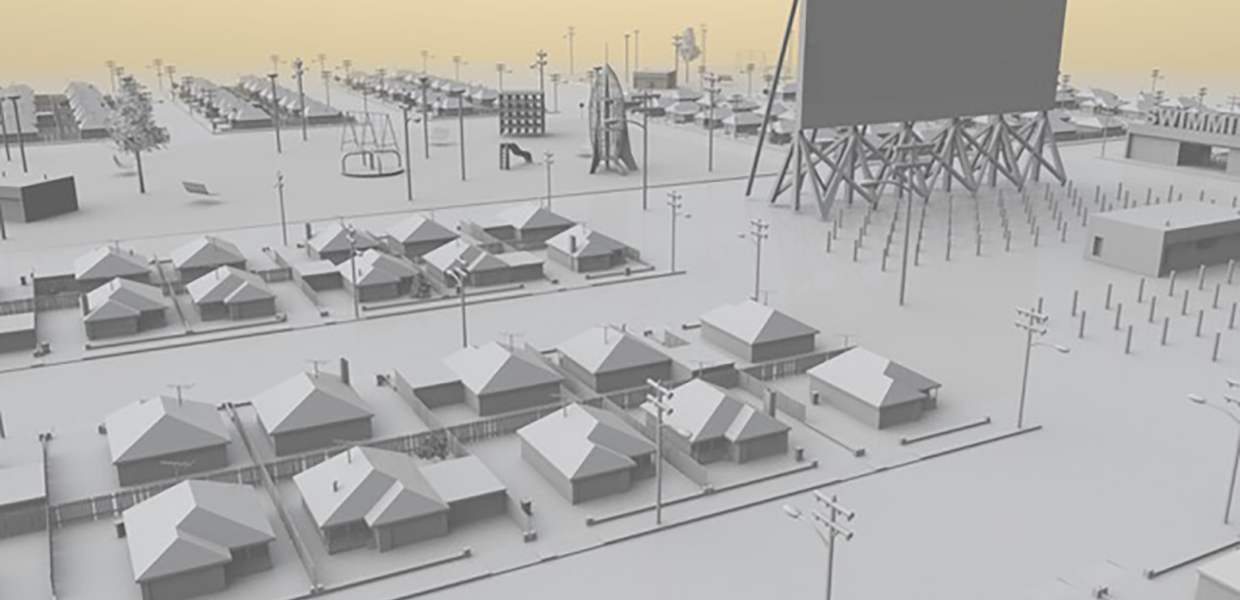

Image | Swimming Pool, urbanansuburban (3D Animation Still, 2012). Artist David Pledger; Image Greg Ferris